By Michael Chung

Etymologically, the term “chaebol” comes from the roots “chae,” meaning wealth, and “bol,” meaning clan or faction. Historically, however, the firms themselves are rooted in the Korean War and Japanese occupation.

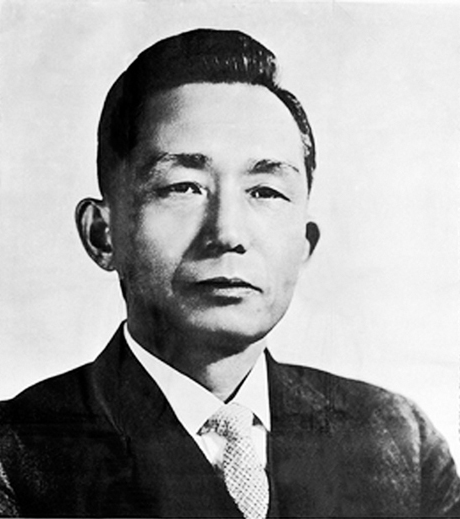

With the end to both the war and foreign occupation in 1943 and ‘45, respectively, many Korean businessmen inherited the assets of Japanese firms operating in Korea. These new, and now Korean, businesses went on to flourish during the 1940s and ‘50s. Allegedly, however, several of these firms had received special government favors in exchange for kickbacks during Rhee Syng Man’s First Republic. Thus, when military leaders, led by Park Chung Hee, overthrew the government in 1961, they pledged to eradicate the crime and exploitation associated with Rhee’s administration.

Park, in particular, targeted firms with close ties to Rhee – firms, which, in hindsight, were the first semblances of “the chaebol.” However, at the time, South Korea’s economy was still small and predominantly agricultural. Park, burdened with the task of rebuilding the war-torn nation, realized that he would, in fact, need these businessmen to help industrialize Korea and modernize its economy. Consequently, the newly appointed chairman compromised with the chaebol heads, allowing them to pay fines in lieu of prosecution. Additionally, he distributed incentives, ranging from imported raw materials to bank loans, in order to regulate the market and prevent foreign competition – all major objectives of his Five Year Economic Plan. As a result, by the mid-1960s, Park had successfully spurred rapid industrialization; however, as a consequence, the chaebol, bolstered by government loans, had also become significant players in the Korean economy.

It is important to note that, by leading the industrialization of Korea, the chaebol developed a monopolistic/oligopolistic hold over the market. Interestingly, though, this monopolization was fostered by the government, which encouraged the firms to venture into and develop new markets and industries. For example, in the 1950’s and early 60’s, the chaebol were predominantly producing wigs and textiles. However, this all changed when government leaders, seeking to shift the focus of Korea’s economy, turned to the chaebol with a deal in hand – the firms were to turn their focus to defense, chemicals, and heavy industries, and, in return, would be rewarded with public projects and access to foreign loans and technologies.

Indeed, by the mid-1970s and ‘80s, the chaebol, lured by incentives, diversified their operations, and, again, aided by government benefits, expanded their influence on the economy. By the late 1980s, their thereupon explosive growth allowed them to become financially independent, eliminating their need for government-sponsored assistance; and in the 1990’s, they concentrated their growth on electronics and high technology, boosting South Korea’s standard of living to a level comparable to that of most other industrialized nations. However, at the same time, government leaders began to fear that the chaebol were becoming too powerful, and increasingly began to challenge them, albeit unsuccessfully, with litigation. The chaebol, evidently, had gained too much financial and political leverage, and would not seem vulnerable again until the arrival of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis (commonly referred to as the IMF Crisis here in Korea).

At the time of the crisis, many of the chaebol had been aggressively taking on loans in bids to expand their global operations. Caught off guard by the sudden crunch in credit, 11 of the 30 largest chaebol collapsed under the weight of their own debt. Amongst those that failed were Kia Motors, which was eventually bought out by Hyundai; Samsung Motors, whose $5 billion venture was dissolved; and Daewoo Motors, which had approximately $80 billion in debt – marking the largest corporate bankruptcy in history. In the aftermath of the crisis, the Blue House seized an opportunity to rein in the chaebol and passed a series of aggressive regulatory changes. These included increased minimums for outside directors on company boards, stringent accounting rules, and mandatory auditing committees – all changes that sought to improve governance and block the “backdealing” nature of chaebol operations.

However, in the years that have followed, the government has struggled to keep the chaebol – particularly the chaebol heads – in check. In 2012 alone, Kim Seung Yeon, the chairman of Hanwha Group, was investigated for embezzlement, and Chey Tae won, the chairman of SK Group, was indicted for the disappearance of 99 billion KRW. Additionally, Lee Kun Hee, chairman of Samsung Group, was found guilty of tax evasion in 2009, and S.R. Cho, chairman of Hyosung Group, has been indicted on similar charges this very year. More surprising than the charges themselves, however, is the fact that many of the punishments were never served. Chey, convicted of a separate accounting fraud in 2003, was pardoned in full and later chosen to represent Korea during the G20 summit. Similarly, Lee Kun Hee was given a full pardon for his crimes, which stirred speculation that he was given preferential treatment due to his involvement in Korea’s bid for the 2018 Winter Olympics.

While incidents like these may seem unfathomable to those on the outside, they are actually quite consistent, given the long-standing history between chaebol and nation. In a sense, the chaebol have always been brash in their pursuit of self-interest, often drawing the ire of the Blue House – and the public – for their propensity to circumvent the law. However, historically, the South Korean economy, from inception, has always been tied to the success of the chaebol, creating a rather complex “push-pull dynamic” between government leaders and chaebol heads. Thus, while South Korea’s economic future remains somewhat murky in light of the slow economy, if history has shown us anything, it is that there is at least one thing for certain – whatever that future may be, the chaebol and their chairmen will be inextricably tied to the center of it.

References:

Ahn, Choong-yong. “Chaebol Powered Industrial Transformation.” Koreatimes.co.kr. The Korea Times, 30 Apr. 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. URL: http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/biz/2010/09/291_65162.html

Chekan, Kate. Korea and the Great Recession: The Effects of Chaebol Reform on South Korea’s Recovery from the 2008 Financial Crisis. SAIS US-Korea 2010 Yearbook. U.S.-Korea Institute at SAIS, n.d. Web. 31 Mar. 2014.

“The Chaebol Conundrum.” The Economist. The Economist Newspaper, 03 Apr. 2010. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. URL: http://www.economist.com/node/15816756

“Minority Report.” The Economist. The Economist Newspaper, 11 Feb. 2012. Web. 25 Mar. 2014. URL: http://www.economist.com/node/21547255

Do you think direct foreign competition is a threat to the Chaebol system?

Apologies for the late reply Ben!

While I believe the issue of foreign competition is somewhat complicated, I don’t think foreign firms a threat to the chaebol. As mentioned in the article, the chaebol have a deep-running history in this country and are essentially synonymous with the modern Korean economy. With this comes a non-insignificant amount of financial, political, and social capital that they are able to leverage towards their best interests. In other words, (though, in light of recent history, I am hesitant to use this term) they are “too big to fail.”

In addition, Korea’s protection of its local industries, coupled with a strong sense of nationalism among its people, make it unlikely, at least in the near future, for the chaebol to go anywhere soon.

Hope that answers your question!